ye masā.il-e-tasavvuf ye tirā bayān 'ġhālib' tujhe ham valī samajhte jo na bāda-ḳhvār hotā - These lofty Sufistic questions! This style of yours, Ghalib! We would have thought you a saint, if you weren’t a wine drinker.1

This is one of the many couplets (sher in Urdu) of Ghalib that define his personality. The context of this sher is important and it can be understood only by comprehending the sher which precedes it. Ghalib writes –

usey kaun dekh saktā kih yagānā hai woh yaktā jo dūī ki bū bhi hotī to kahiñ do chār hotā - Who can see Him? For that oneness is unique. With even a whiff of twoness, then somewhere—an encounter.1

Ghalib has so wonderfully played with numbers in this sher. He says that we have not seen Him (God) yet since He is the only one there is and He is alone. Had there been two gods, would not either of them have come forward [to claim their godship]?

Mirza Beg Asadullah Khan, known by his nom de plume – Ghalib (or Mirza Ghalib) was born on 27 December 1797 in Agra to Abdullah Beg Khan and Izzat-un Nisa Begum, an ethnic Kashmiri. His grandfather, Mirza Quqan Beg Khan, came to India from Samarkand in the 1750s2. Ghalib began writing poetry when he was around 11 years old; he used ‘Asad’ as his pen-name initially.

Ghalib served in the court of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. He was not the only brilliant poet in the court, and surprisingly not considered the best. There was Ibrahim Zauq, the poet laureate of the Mughal Court. There was another brilliant poet, Momin Khan Momin. Among Momin’s most popular ghazals is – “wo jo hum mein tum mein qarar tha tumhein yaad ho ki na yaad ho” which was later sung by Begum Akhtar. And, there was Bahadur Shah Zafar himself.

Ghalib had a turbulent life, full of poverty and tragedies. He married the daughter of Nawab Ilahi Baksh, Umrao Begum, when he was thirteen. They had seven children together but none of them lived for more than 15 months. He had no source of income other than his pension, which was reduced to half by the East India Company. He even went to Calcutta (now Kolkata) in a bid to appeal to the company that his full pension is restored. The journey was arduous. Finally, Ghalib arrived in Calcutta on 19 February 1828 and spent almost a year and a half in Calcutta. He rented a house for a rent of mere 6 rupees per month. The address was: Haveli of Mirza Ali Saudagar, Gol Talab, Shimla Bazaar3. He established himself as a personality of great prowess. Ghalib describes his love for Calcullata in this verse:

kalkatte kā jo zikr kiyā tū ne ham-nashīñ ik tiir mere siine meñ maarā ki haa.e haa.e - As you mentioned Calcutta to me, O Companion! Ah, it is as if you shot an arrow in to my chest.

![House no. 133, Bethune Row, the building where Ghalib stayed in Calcutta. [Source: Rana Safvi's Twitter Thread]](https://danishshakeel.me/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Eqvrx9eVQAAMlvi-1024x1024.jpeg)

Ghalib returned to Delhi in November 1829.

He describes life and marriage as a form of imprisonment.

qaid-e-hayāt o band-e-ġham asl meñ donoñ ek haiñ maut se pahle aadmī ġham se najāt paa.e kyuuñ - The prison of life and the bonds of grief—in essence, both are one. Before death, how could a person be freed from grief? 1

The matlaa (first sher of a ghazal) of this ghazal enunciates and summarizes Ghalib’s feelings (about life) even better.

dil hī to hai na sang-o-ḳhisht dard se bhar na aa.e kyuuñ ro.eñge ham hazār baar koī hameñ satā.e kyuuñ - It’s a heart, after all, not stone or brick—why wouldn’t it fill up with grief? I will weep a thousand times—why would anyone torment me?1

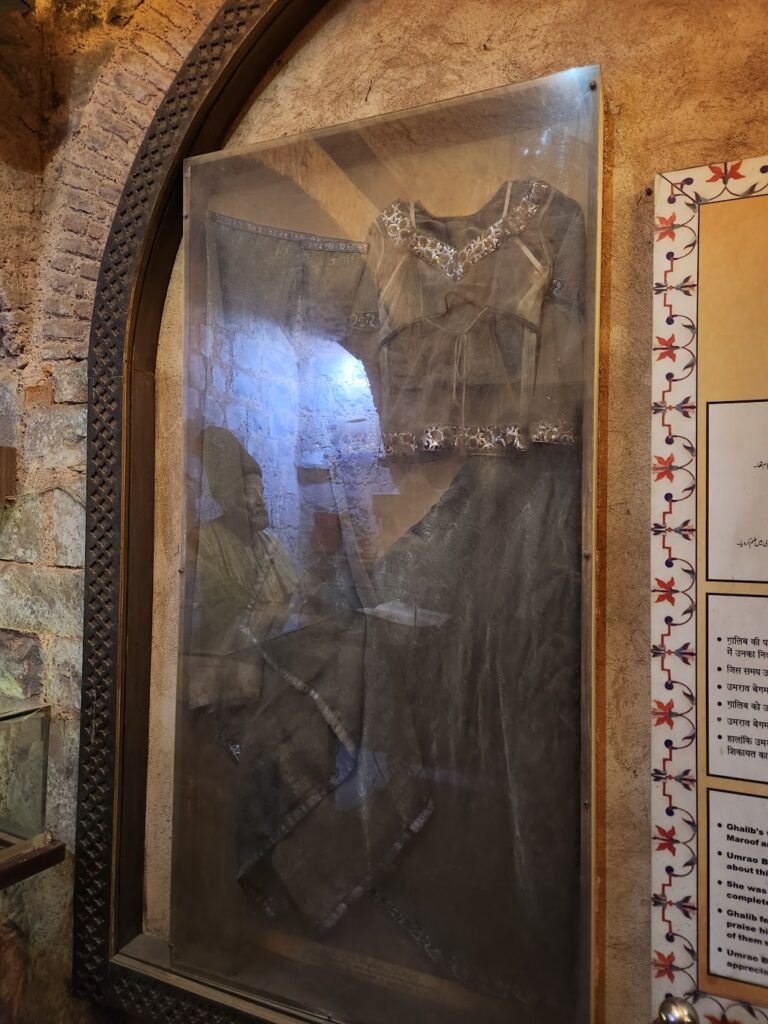

Although the indicators about their marriage are not aplenty, it is known that both had polar opposite views about religion. Umrao was a devout muslim, and Ghalib, in his own words was ‘half’ muslim. Half — for he drank wine but did not eat pork. Despite their ideological differences, they remained together till Ghalib’s death in 18694.

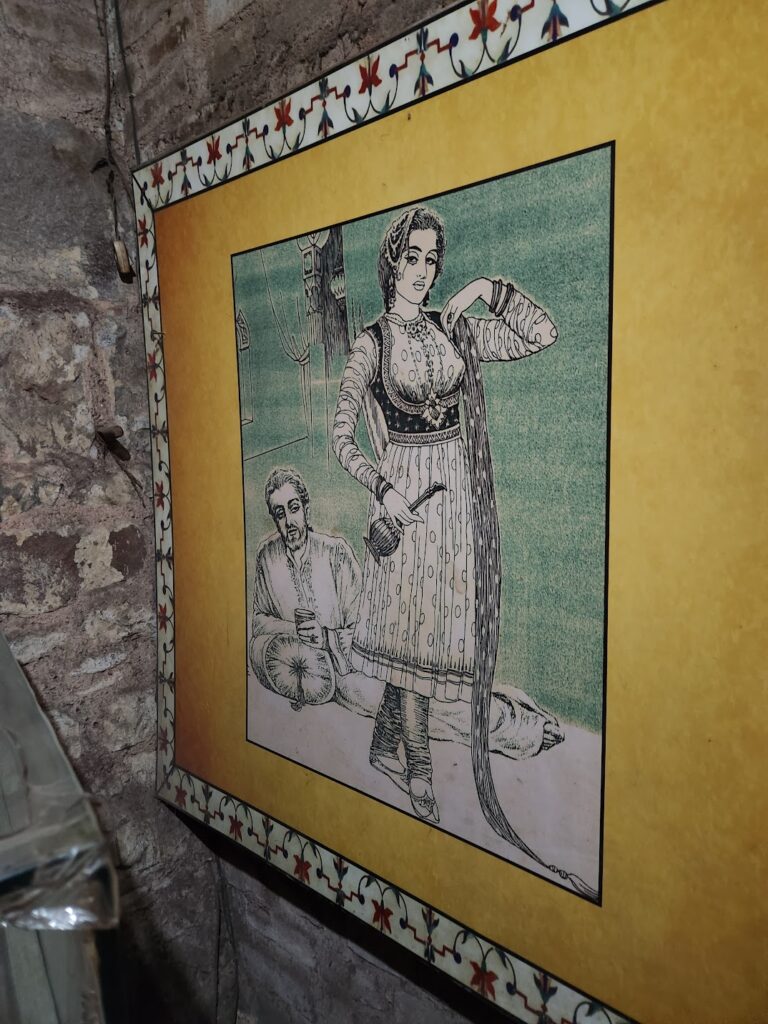

All lovers are not poets, but all poets are lovers; it takes a heart-break to turn you into a poet (in my opinion) and agonies to turn you into a poet like Asad. Ghalib confessed to have been in love with a dancer (ḍomnī), Mughal Jaan, in his letter to Hatim Ali Mihr in 1860. The love, pain, and regret oozes in his poems and letters.

Ghalib was well-aware that the relationship would never progress. Although, there was a romantic inclination, Ghalib had to honour the circumstances; also, Mughal Jaan did not live long enough for their love to ripen. One of my favourite verses about their love:

vaañ vo ġhurūr-e-izz-o-nāz yaañ ye hijāb-e-pās-e-vaza.a raah meñ ham mileñ kahāñ bazm meñ vo bulā.e kyuuñ - there - the beloved has pride in her grandeur and coquetry, here - this modesty/'veil' of regard for character/dignity why/how would we meet in the road? why/how would she invite me to a gathering?1

This sher describes the state of their love and is full of nuances, like vaan (there) is opposite to yaan (here) as raah (road) is opposite to bazm (gathering). Ghalib says that the beloved is too proud and arrogant to invite such a humble person to a lofty social occasion. hijab can be an intentional diversion; either Ghalib wants to say that he is modest, that he actually respects his character and the social norms, or the word implies a ‘veil’ of modesty – that he does not actually wish to conform to these rules, but has to. In either of the cases, their meeting is rendered impossible.

Ghalib is known for his contribution to the Urdu language, but Ghalib was also fond of writing letters. He loved Farsi. His 800-plus letters are compiled in a seven-volume collection called Khutoot-e-Ghalib (Letters of Ghalib).

In a letter of condolence to Mihr(1860), he writes about Mughal Jaan:

bhai, mughal-che bhi gazab hote hai. jis par marte hain usko maar rakhte hai. mai bhi mughal-cha hun. umr-bhar mein ek badi sitam-pesha domni ko maine bhi maar rakha hai. - My friend, we Mughal types are devastating — the one whom we’re dying for, we end up killing. I too am a Mughal type. In the course of my life I too have killed a very cruel dancing girl1.

Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a turning point, for Delhi and for Ghalib. The revolt was given countenance by Bahadur Shah Zafar. The revolt was eventually supressed by the British Empire in 1859 and Bahadur Shah was exiled to Rangoon, Burma. Ghalib writes in a letter to Tafta (1857):

Let no one think that I’m dying of grief over my own dismal and ruined state. The sorrow that I feel, I can’t at all express; but I can give a hint of it. From among those of the English community who were murdered at the hands of those disgraced [“black-faced”] black ones, one was my patron, and one was my well-wisher, and one my friend, and one my supporter, and one my pupil. Among the Hindustanis, some dear ones, some friends, some pupils, some beloveds. Thus every one of them was mingled with the dust. How harsh is the mourning for one dear one! He who would be a mourner for so many dear ones—how could his life not be difficult? Alas! So many friends died that now when I die, there won’t even be anyone left to mourn for me1.

During the revolt, Ghalib lost most of his writings as his friends’ houses were looted. In his letter to Mihr (1858), he writes about his loss:

I never kept my poetry with me. Navab Ziya ud-din Khan and Navab Husain Mirza used to collect it. What I composed, they wrote down. Now both their houses have been looted. Libraries worth thousands of rupees were destroyed. Now I long to see my own poetry. A few days ago a faqir, who has a good voice and is a fine singer too, found a ghazal of mine somewhere and got it written down. When he showed me that piece of paper, believe me, I felt like weeping. I send you the ghazal, and as a reward for it I want an answer to this letter1.

![The Last Mughal Renaissance [Source: Open The Magazine]](https://danishshakeel.me/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/19866.lastmughal1.jpg)

Ghalib’s last years were full of illness, suffering, and poverty. One evening, Sayyid Sardar Mirza visited Ghalib. As he was leaving, Ghalib brought the candle with the edge of the carpet so that he can put on his shoes. Sayyid said: “Your Worship, why have you taken the trouble? I would have put my shoes on by myself”, to which Ghalib replied: “I brought the candle not to show you your shoes, but for the fear that you might put on mine by mistake!”1,4

He breathed his last on 15 February 1869. Ghalib evaded love (Valentine’s week) once again! He lived the final phase of his life (1860 – 1869) in a haveli in Gali Qasim Jan, Ballimaran, Old Delhi. The place served as a heater factory but was declared a heritage site after its possession was ‘recovered’ by the government in the late 1990s. He is buried near the Dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin. Umrao died a year later, in 1870.

References

- ‘Ghalib: Selected Poems and Letters (Translations from the Asian Classics)’ by Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Frances Pritchett, et al.

- ‘Aḥmad Shah | Mughal emperor’, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ‘Ghalib: A Wilderness At My Doorstep’ by Mehr Afshan Farooqi

- ‘Yadgar-e-Ghalib’ by Altaf Hussain Hali